Fortune, Sex, and a Good Death: The Bat in Chinese Symbology

A symbol of Fortune, Sex, and a Good Death. The bat is all of these in the Chinese culture, these facts were unknown to myself when I had the illustration of an Eastern Grey Flying Fox tattooed to my chest. I had chosen the image as for me, it is a symbol of the bush, of home. Of course, it didn’t hurt that my other, very western associations were of horror, the gothic, grim fairy tales and demonic wings, an aesthetic and genre I’ve long been enchanted by. In the days following, our Principal and my mentor, Shifu Tara encouraged me to read about the Chinese beliefs surrounding bats; what I found was a stark contrast that has made me even more enamored by these auspicious creatures.

A “True Name” is an ancient philosophical idea, that the very name of a thing can entirely summarise or is somehow identical to its true nature or being. This is exceptionally true for the bat in Chinese culture. The Chinese words for bat and fortune demonstrate a direct homophonous relationship; the Chinese characters for bat 蝙蝠 pronounced “biānfú”, is incredibly similar to the Chinese character for fortune 福 and is also pronounced “fú”. To say the word bat, is to literally speak of fortune, as does the sight of a bat flying overhead mean quite literally that fortune has flown into one’s life. This idea encapsulates the very poetic Chinese notion that good fortune can fly into one’s life at any time and unannounced.

There is an ancient tradition not only in China but worldwide, wherein practices and behaviors of animals form symbols that are venerated, near worshipped for hope of bringing those qualities into an individual’s life. In Wushu for example, these animal behaviors are replicated and form cunning styles, consider crane style, monkey style; in our tai chi we perform the movements of “Snake Creeps Down”, “Parting the Horse’s Mane” and “White Crane Flashes its Wings”. The bat is no exception to this practice; they are known for their way of hanging upside down and remaining still at great lengths, an admirable quality in eastern cultures, as it symbolizes patience, meditation and a stillness that brings about long life and a good death. All of these behavioral qualities are compounded by the alliteration of their namesake; the bat not only enjoys a long life, but does so in a way of blessings or good fortune. Because of this the bat is revered as a kind of otherworldly being, they appear to live forever in the unexplored parts of the world, meditating in immortal stillness yet capable of taking into the heavens upon a whim.

The symbolism and associations of the bat are demonstrated in a quite literal, linguistic and behavioral sense, and therefore it naturally follows they are celebrated visually in art and culture.

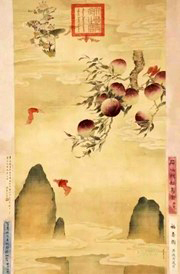

Pictured here is a painting by Qing Dynasty Emperor Tongzi, titled “Bat and Peach”, the palette is of warm and soft pinks and reds with gentle contrasts to the green mountains below. It is important to note the bat stands as a predominant symbol of masculinity; often in eastern cultures the world is viewed through the lens of constant interaction between opposite yet related elements, masculine and feminine, good and evil, the very elements themselves and of course, Yin and Yang. Peaches in ancient Chinese culture represent a symbol of female fertility (fascinating how history repeats itself by way of the peach emoji in our modern era, for those in the know). The two are often depicted together as a subtle sex symbol of feminine and masculine interplay, cleverly disguised as a demonstration of the ecological relationship between bat and peach. Peaches are estimated to have first been propagated by the Chinese some 5000 years ago, prior to which the ancient Chinese depended on the bats to taste of the fruit and spread the seeds far. These depictions between bat and peach are so commonplace that the bat itself is often associated as a symbol for sex, regardless of whether peaches are depicted.

Pictured here is a painting by Qing Dynasty Emperor Tongzi, titled “Bat and Peach”, the palette is of warm and soft pinks and reds with gentle contrasts to the green mountains below. It is important to note the bat stands as a predominant symbol of masculinity; often in eastern cultures the world is viewed through the lens of constant interaction between opposite yet related elements, masculine and feminine, good and evil, the very elements themselves and of course, Yin and Yang. Peaches in ancient Chinese culture represent a symbol of female fertility (fascinating how history repeats itself by way of the peach emoji in our modern era, for those in the know). The two are often depicted together as a subtle sex symbol of feminine and masculine interplay, cleverly disguised as a demonstration of the ecological relationship between bat and peach. Peaches are estimated to have first been propagated by the Chinese some 5000 years ago, prior to which the ancient Chinese depended on the bats to taste of the fruit and spread the seeds far. These depictions between bat and peach are so commonplace that the bat itself is often associated as a symbol for sex, regardless of whether peaches are depicted.

Shown here is a much more contemporary illustration of bats, reminiscent of the bright and happy symbols used for Chinese New Year. Note the five bats circling the image of a gate. Five (pronounced Wǔ) is an important number in Chinese culture and considered very auspicious due to its parallels to the 5 elements, which are all essential for fostering a good life if kept in good balance. Bats shown in fives symbolize the Chinse idea of “wǔfú” (translating literally to “five blessings”), that there are five major aspects of good luck and fortune; to achieve one form of fortune is to bring oneself closer to the other four forms. The image above is the demonstration of “wǔ fú lín mén”, translated to “May the five blessings (longevity, wealth, health, virtue and a natural death) come to you”. An expression that becomes increasingly popular during the time of Chinese New-Year, it is also commonplace to see many doors and gates decorated with five bats across China. We also see the image of a bat appear in our Wushu and Tai Chi weaponry; the guard of a sword, engraved on the blades of long weapons, on scabbards, and clothing.

Shown here is a much more contemporary illustration of bats, reminiscent of the bright and happy symbols used for Chinese New Year. Note the five bats circling the image of a gate. Five (pronounced Wǔ) is an important number in Chinese culture and considered very auspicious due to its parallels to the 5 elements, which are all essential for fostering a good life if kept in good balance. Bats shown in fives symbolize the Chinse idea of “wǔfú” (translating literally to “five blessings”), that there are five major aspects of good luck and fortune; to achieve one form of fortune is to bring oneself closer to the other four forms. The image above is the demonstration of “wǔ fú lín mén”, translated to “May the five blessings (longevity, wealth, health, virtue and a natural death) come to you”. An expression that becomes increasingly popular during the time of Chinese New-Year, it is also commonplace to see many doors and gates decorated with five bats across China. We also see the image of a bat appear in our Wushu and Tai Chi weaponry; the guard of a sword, engraved on the blades of long weapons, on scabbards, and clothing.

Depictions and meaning behind the bat’s symbology are myriad across cultures and time. The one constant across these different cultures is its imposing etherealness; whether it be The East’s love for the Bat’s timeless meditation, its endeared heralding of good luck and sultry hypermasculine energy; or the West’s provocative connections to hellscapes and demon wings - The Bat remains a magical, otherworldly symbol.

This is the first in a series of articles on Chinese mythology, religion, and symbolism by our own Tristan Davenport.

Recent Posts

- Why We Teach Ba Duan Jin Health Qigong

- Why the Wǔ Symbol is so Important to Anyone Practicing Chinese Martial Arts

- The Year of the Fire Horse – Ride it without Fear

- Caring for the Self

- Eight Energies, Five Steps, Two Weeks, and a Lifetime of Practice: Training at Beijing Sports University 2025

- Qigong: A Guide to Understanding the Many Paths of Energy Cultivation

- The Year of the Wood Snake and Tai Chi/Qigong: A Harmonious Interplay

- An Introduction to the Six Harmonies in Taijiquan

- Tai Chi Lessons from a Broken Piano: Work with What You Have

- Tai Chi and Cage Fighting: Zhang WeiLi, China’s UFC Champion

Tags

Archive

- March 2026 (1)

- February 2026 (1)

- January 2026 (1)

- December 2025 (1)

- November 2025 (1)

- March 2025 (1)

- January 2025 (1)

- November 2024 (1)

- September 2024 (1)

- July 2024 (1)

- January 2024 (2)

- December 2023 (1)

- September 2023 (1)

- June 2023 (2)

- April 2023 (1)

- January 2023 (2)

- November 2022 (1)

- August 2022 (1)

- March 2022 (1)

- January 2022 (2)

- September 2021 (1)

- May 2021 (1)

- March 2021 (1)

- February 2021 (2)

- January 2021 (1)

- December 2020 (1)

- August 2020 (1)

- April 2020 (1)

- January 2020 (1)

- October 2019 (1)

- May 2019 (2)

- April 2019 (1)

- March 2019 (3)

- February 2019 (2)

- January 2019 (3)

- December 2018 (2)

- October 2018 (1)

- July 2018 (1)

- June 2018 (1)

- April 2018 (2)

- February 2018 (1)

- October 2017 (1)

- September 2017 (1)

- April 2017 (2)

- March 2017 (1)

- January 2017 (2)

- December 2016 (2)

- October 2016 (1)

- September 2016 (1)

- August 2016 (1)

- July 2016 (2)

- June 2016 (21)